The DreamerV2 model

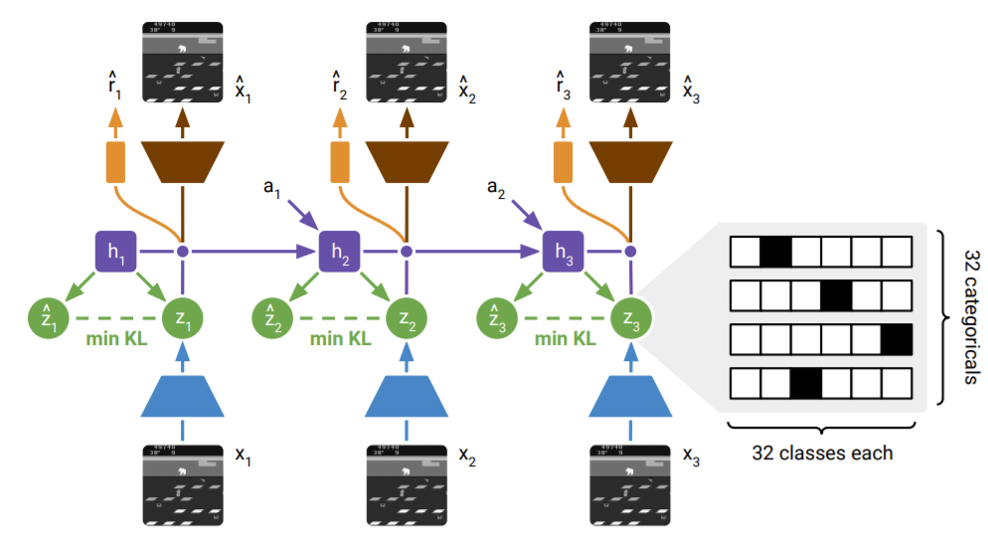

DreamerV2 ( Citation: Hafner, Lillicrap & al., 2021 Hafner, D., Lillicrap, T., Norouzi, M. & Ba, J. (2021). Mastering Atari with Discrete World Models. 9th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2021, Virtual Event, Austria, May 3-7, 2021. Retrieved from https://openreview.net/forum?id=0oabwyZbOu ) is a reinforcement learning agent that builds a world model of it’s environment, trained separately from the policy. The agent attains human-level performance on the Atari benchmark, and serves as the first model-based approach to do so. An interesting aspect of this world model is that it’s partially discretized. The latent representation of the world model consists of a continuous memory portion, and a discretized portion represented by 32 categorical variables, each of which has 32 categories (i.e. 32 one-hot vectors of length 32). The world model architecture is demonstrated in the figure below, taken from the DreamerV2 paper.

The continuous latent $h_i$ is represented as the purple line, it serves as the memory that is carried over between states. The discrete latent $z_i$ is shown in green, and represents a combination of information from both the continuous memory state and encoded input image. In this figure, the purple dot connecting $h_i$ and $z_i$ is a concatenation operator, thus the policy, image decoder, and reward predictor take a combination of continuous and discrete values, the latent state is not fully discretized as the paper might imply.

Our objective

We aim to evaluate whether representing the latent state as categorical variables encourages the ‘disentanglement’ of concepts learned by the model. While full disentanglement is likely not occuring, we will evaluate how different concepts are represented in the discrete latent representation to identify how the categorical variables may be benefiting the representation and obtain insight into what inductive biases may encourage better disentanglement.

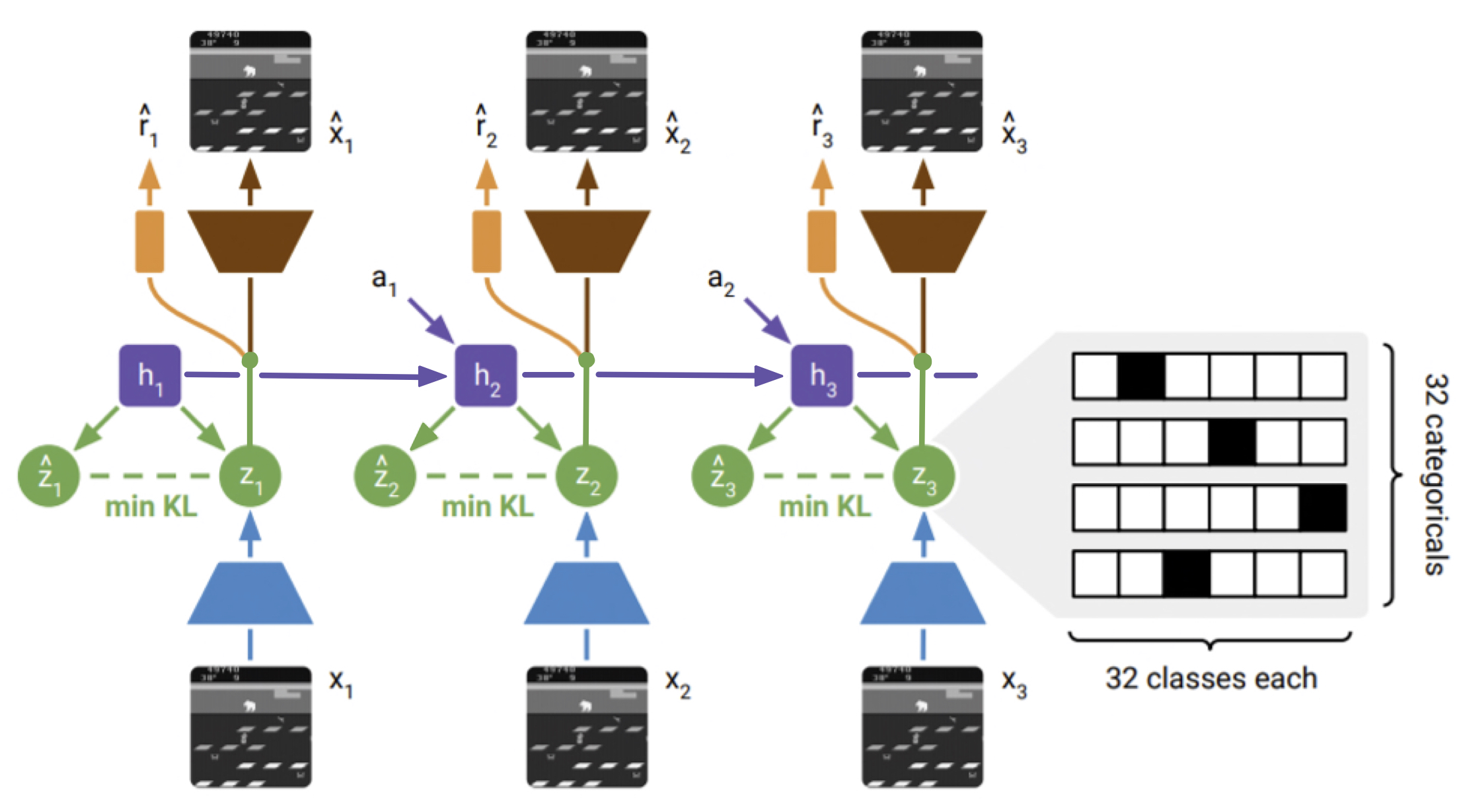

Our modification

As the model is not actually fully discrete, we first modify the agent to have a fully discrete latent representation. This is done by simply changing the concatenation operation. Instead of concatenating continuous and discrete components and passing the concatenation on to the reward, decoder, and policy predictors, we only pass on the discrete component. The continuous hidden state $h_i$ is still passed along as a memory state, but its only usage is in the generation of the discrete latents $z_i$ and $\hat{z}_i$. The updated architecture is demonstrated in the diagram below.

The result is a model that trains much slower and never reaches a perfect policy for Pong after ~25M world steps, when the model with the continuous component should be capable of learning a near perfect policy in this same number of training steps. Due to the compute constraints of our system, we are unable to explore whether there are tweaks that can be made to improve performance of the fully discrete model, so all settings are the defaults found in the code provided by the authors here. This could be an area of improvement in future work, as there may be more ideal experimental settings for training a discretized representation.

Experimental setup

We trained the discretized model to around 25M world steps on the domain Pong. As stated in the previous section, a perfect policy is not learned within this number of training steps, and little improvement was seen after ~20M steps. Although this is unideal it does not necessarily hinder our objective, as we aim to discover how concepts end up represented in the latent state, and we may gain insight into how we can improve the training process for this type of latent representation. To evaluate, we examine the discrete latents along with their corresponding input images provided to the model, thus we have frames of the gameplay along with the discrete internal states of the agent. We collect this data from evaluation episodes that occur as the model is training.

Evaluating the latent space

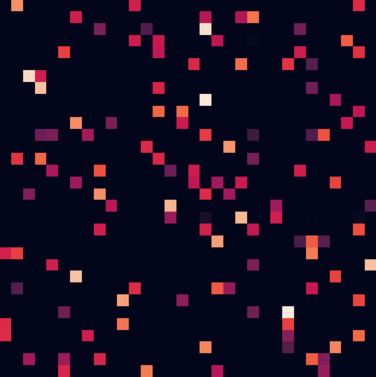

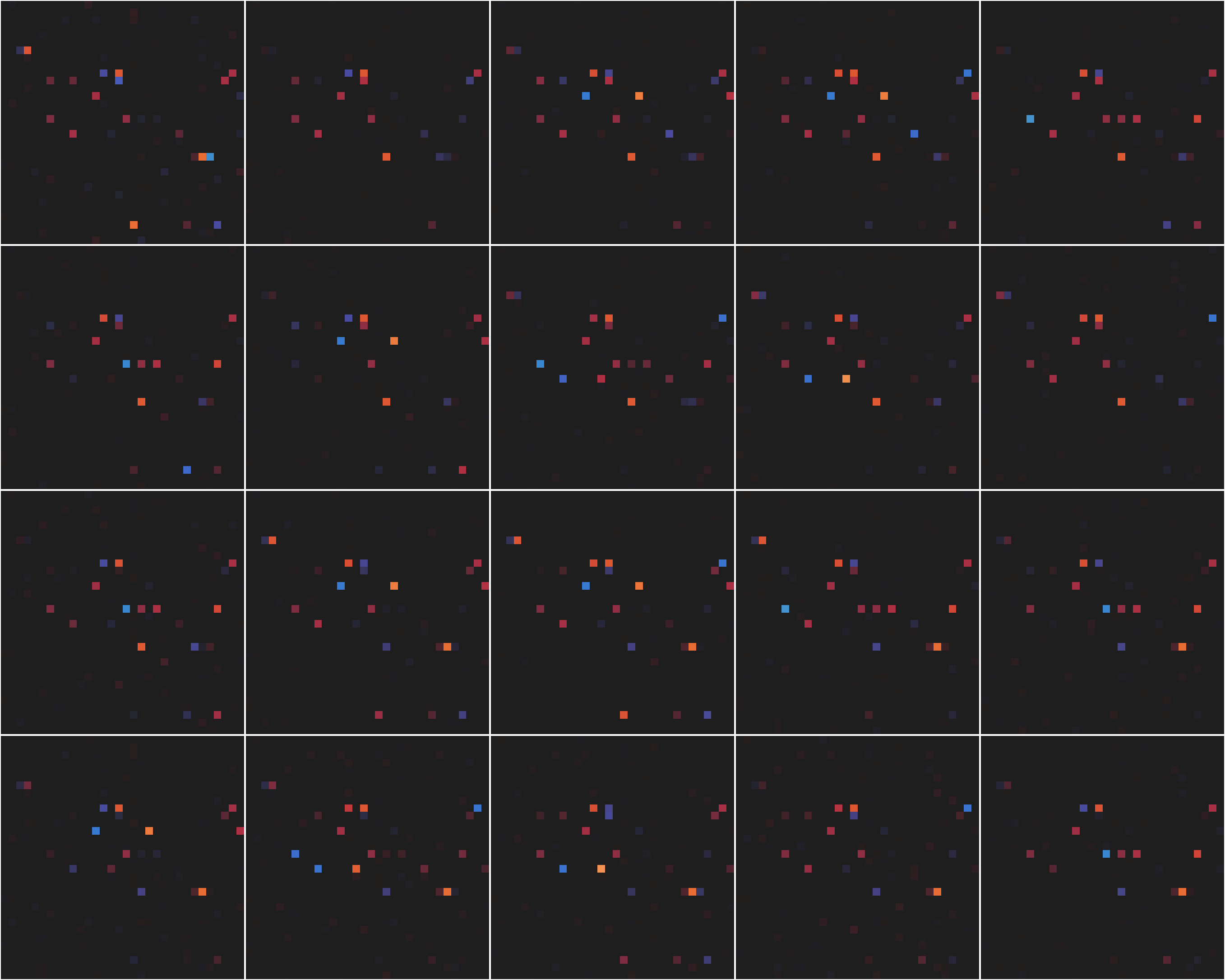

First we examine how the latent space is utilized. We take all latent states that occured over the course of ~160 games of Pong and we sum them, obtaining a count of how many times each variable category was activated over all observed games. The result is a surprisingly sparse image.

Here each row represents a categorical variable, then columns correspond to the categories of each variable. Bright squares represent a frequently activated category, while dark squares indicate low activity. We note that the majority of squares appear black. Not only are they infrequently used, the actual counts tend to be 0. Thus instead of refering to rare and important events in the game, they are simply never utilized by the model. Each variable appears to only utilize a smaller subset of its possible categories, leading to a sparsely utilized latent space.

Changing single variables

In order to determine if there are any identifiable concepts that correspond to categorical variables, we evaluate how the decoded image changes as a single categorical variable is altered through all possible categories. We select one categorical variable, iterate through all categories one at a time, decode the resulting latent state, and save all resulting images as a gif. Below we demonstrate some of the results obtained from one such experiment.

In the top left gif almost no changes can be observed aside from small amounts of noise around the ball. This is what is observed for the majority of categorical variables, very few single variable changes seem to result in visible changes after decoding. In the next three gifs we see examples of decoded latents that do change with the changing of a single categorical variable. While the top right image looks like it may just be due to noise, it appears that this variable may be vital for placing the right paddle in the correct position. In the bottom two figs we observe changes to the left side score. In the bottom left gif, most categories of the altered categorical variable appear to correspond to a 1 in front of the score, changing it from 2 to 12. For the bottom right gif, we see that most categories seem to correspond to a left score of 3. We also briefly see a score of 1, and the original score of 2. An experiment that is currently missing from here is determining if changing these same variables for other latents results in the same effects.

A limitation to this experiment is that it only takes into account visible changes in the decoded image. In future versions of this experiment we may also consider seeing how the predicted action changes based on changes to the latent state. It may also be interesting to set up an experiment where we only change variables between categories that are actually utilized (as demonstrated in the earlier heatmap) and we could use the trained probes from later on to identify whether the predicted location or direction of the ball changes. This may be explored in future work.

Interpolation experiments

Next we evaluate the latent representation for its ability to interpolate between two distant states. A desirable property may be a smooth transition between two latents as we start from one and change the categorical variables over one by one to match the second latent, slowly transitioning to the latter state as we do so. We perform the experiment by doing just that, changing a single categorical variable of the first latent at a time to match the variables of the second latent. The results are demonstrated below.

We find that there is little meaning in the interpolation. An interesting next direction to go in may be to find inductive biases that encourage better interpolation. Overall, we’ve identified that there’s a lot of sparsity in the learned latent space. Not only are few categories of the variables actually utilized, but in performing these interpolation experiments we also observe that combinations of these utilized variables (in the ‘in between’ states) are also not necessarily meaningful.

Score evaluation

The previous experiments hint at a complex embedding of game concepts. We explore this deeper by evaluting how game score information is stored in the representation. While this information isn’t necessary for the policy, it is required to reconstruct the input image, thus must be encoded in the representation in some way. First we examine statistical differences in the average categorical activations for each score compared to the average utilization across all scores.

While it is not exactly clear what these differences mean, it’s clear that the patterns displayed appear to differ between scores. Thus scores may be represented in the representation in a quite complex manner.

Probing

Next, we probe the learned representation by training neural networks to predict a given concept given the latent state as input. Here we test whether we can predict the X and Y coordinates of the ball, and its horizontal and vertical velocity. Our hypothesis is that this information should be vital for the policy to accurately predict where to move the paddle, as the agent should be able to find the ball and compute its trajectory towards the paddle.

To gather the data we collect latent states that occur as the ball is moving towards the agent’s paddle. We track the ball as it moves across the screen to determine its position and velocity, and only take those with a positive horizontal velocity. We then train several neural networks, starting with a linear layer that consists only of an input and an output layer, and increasingly add hidden layers up to 5 additional hidden layers. We see from the following results that performance scales with the number of layers, significantly increasing after a single hidden layer is added.

| Hidden Layers | X coord MAE | Y coord MAE | Horizontal velocity MAE | Vertical velocity MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.35 | 8.41 | 1.40 | 2.08 |

| 1 | 1.19 | 3.01 | 0.74 | 1.47 |

| 2 | 0.93 | 2.62 | 0.62 | 1.42 |

| 3 | 0.74 | 1.94 | 0.56 | 1.37 |

| 4 | 0.70 | 1.67 | 0.56 | 1.30 |

| 5 | 0.62 | 1.40 | 0.53 | 1.27 |

It appears that the probe could predict the x coordinate and horizontal velocity significantly better than it could predict the y coordinate and vertical velocity.

Conclusion and next steps

This serves as an initial exploration into how DreamerV2 may represent game concepts in its discrete latent space. We found embeddings of concepts to be quite complex, and found the utilization of the latent space to be quite sparse. Meaningful future directions could be to implement priors that allow for a more ‘compact’ representation that encourages meaningful interpolations, as well as explorations on additional domains. A comparison between this version of DreamerV2 with the fully categorical latent space and the original DreamerV2 which has continuous and categorical components is also left for future work.

References

- Hafner, Lillicrap, Norouzi & Ba (2021)

- Hafner, D., Lillicrap, T., Norouzi, M. & Ba, J. (2021). Mastering Atari with Discrete World Models. 9th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2021, Virtual Event, Austria, May 3-7, 2021. Retrieved from https://openreview.net/forum?id=0oabwyZbOu